A friend of mine manages a hosted ecommerce solution and was complaining to me the other day that people in his organization were putting unauthorized code onto production servers without going through the typical deployment process. His team would discover this when upgrading the customers’ ecommerce sites. During the upgrade, they would stumble across some utility that was created to help the customer import data, generate a report, create shopper accounts, etc.

A friend of mine manages a hosted ecommerce solution and was complaining to me the other day that people in his organization were putting unauthorized code onto production servers without going through the typical deployment process. His team would discover this when upgrading the customers’ ecommerce sites. During the upgrade, they would stumble across some utility that was created to help the customer import data, generate a report, create shopper accounts, etc.

This was causing him three major headaches:

- The utility would fail when run against upgraded codebases or data structures. Because it was slipped in without any documentation or tracking, fixing the broken utility was a major hassle.

- These utilities were written to address a specific need of a single customer, but they were never considered as a possible enhancement to the product offering for all customers.

- They were done as a favor to the customer at no charge!

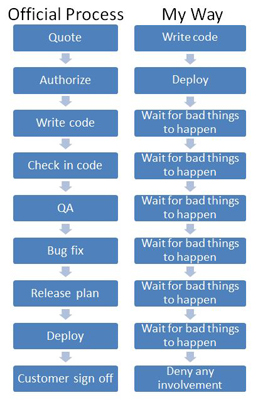

After he explained the situation that was causing him frustration, I asked if he had a process that people were supposed to follow to deploy code on production servers. He explained that the process involved:

- Quoting the cost to the customer

- Customer authorization

- Writing the code

- Checking it into the software versioning control database

- QA cycles

- Bug fix cycles

- Release planning (time, mechanism, packaging, etc.)

- Deployment

- Final customer sign-off

Then I asked him if this process was documented. He admitted that it was not, but that “everyone” knew about it. My response was that he didn’t have a process, he had a hobby.

The definition of a process is a DOCUMENTED sequence of steps by which inputs are transformed to outputs.

He didn’t see the value in having the documentation because the documentation wouldn’t prevent people from bypassing the process.

Process documentation is just the first step in ensuring that you have good controls around critical services. The second step is to set a goal. I proposed that he should set a goal of 97% of all code in the production environment must have been fully vetted through the deployment process*.

With that goal in mind, he needs some way to measure compliance to the goal. At this time, he said it would be difficult since he doesn’t have any mechanism to baseline his production servers to assure that the code base hasn’t been altered. I suggested that he just run “dir /s” on the servers every night and read the last two lines of the output. If those values have changed, and nothing has been authorized for release in the previous 24 hours, someone made an unauthorized change. Record this metric every day and, over time, you have a good Key Performance Indicator (KPI).

Even if there is no way to proactively discover the unauthorized code, it will be discovered eventually. That is, after all, how this conversation started (i.e. finding bits of code on production servers that hasn’t been checked-in and documented).

So let’s take an inventory. I have proposed:

- Document the process

- Establish a critical success factor (CSF): 97% compliance with process

- Put in place a mechanism to measure compliance: dir /s

- Find a way to periodically check your compliance and establish a KPI to determine if you are moving towards or away from your CSF

With these in place, you can now put in something to correct the behaviors that are causing the issues.

This leads us the last major problem he has to deal with. The person who most frequently bypasses the deployment process isn’t support (although they are occasionally at fault), or the programmers. It is his boss stepping in and “helping” a customer with just, you know, a quick fix.

So how can you enforce a process with some teeth when the person who bypasses your process is above (or outside) your sphere of influence? Truth be told, no one is exempt from behavioral corrections. Here is a possible (and humorous) way to modify someone’s behavior:

Penalties for being discovered as having deployed code to the production servers without going through the documented deployment process:

- First time penalty: Your email address will be added to 20 local restaurants’ mailing lists.

- Second time penalty: Your email address will be added to 20 local services’ mailing lists (chiropractic, dentist, windshield glass repair, etc.)

- Third time penalty: Your email address will be added to 20 religious organizations’ mailing lists (no discrimination on denomination or beliefs)

- Fourth time penalty: Your email address will be added to 20 politicians’ mailing lists (all political parties)

- Fifth time penalty: Your email address will be published in Reddit with an open invitation to spam

Although I think that this would be a perfect solution, there are many ways to modify people’s behavior. Some organizations have the “Wall of Shame” that your name gets posted to if you break the rules. Some have a trophy that has to be prominently displayed on their desk. Some require the offender to buy the team lunch every day for the next week. Be creative and find a means to achieve the desired change in behavior that works best in your organization’s culture.

By the way, this is an example of process engineering in a nutshell. Good process engineering focuses on identifying the pain points, setting achievable goals, and producing clear and useful documentation and metrics. You must do all of this before going to penalties for bypassing process. If your organization has penalties without goals, documentation, and metrics – call foul on them.

*Why 97% and not 100%? First and foremost, it is because I hate absolutes. Indeed, if you want to set yourself up for failure, set an absolute goal of 100%. What happens if the key people responsible for the process are unavailable and all the servers go down? What happens if you have to make a single character change because of syntax error in the code that didn’t get discovered in QA? You should include in your process design a mechanism by which the process can be bypassed and by which that bypass can be approved (even if the approval is after the fact).

Leave a Reply